Joanne Kyger

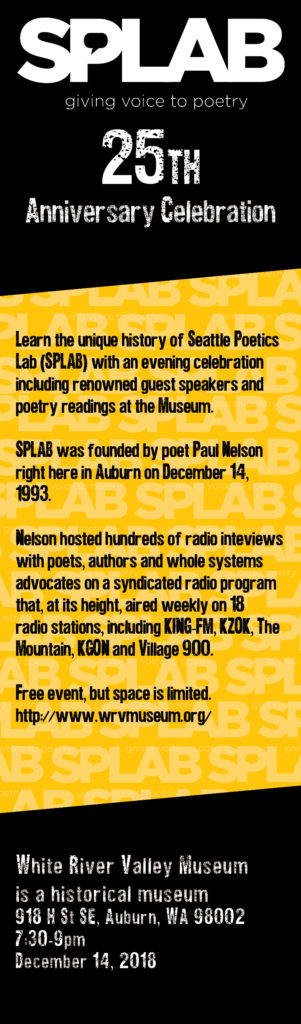

Joanne Kyger is one of the headliners at the 2nd Cascadia Poetry Festival. Because of her involvement in the Spicer Circle/San Francisco Renaissance of the late 1950s, which included poets like Robert Duncan, Robin Blaser and George Stanley (also headlining Cascadia 2) she was invited to read and be on a panel and accepted. The influence of Spicer and Duncan on the Vancouver TISH poets, among others, and Robin Blaser’s long fertile period in Vancouver, BC, suggest it is one of the deepest strains of innovative poetry in the Cascadia bioregion. Jeffrey Kahrs wrote the following piece to spotlight Kyger’s fine poetry. To him and Joanne, we are grateful and present it here to whet your appetite for this under-appreciated West Coast poet.

The Pleasure of Washing One’s Hair

Though there are many delights in Joanne Kyger’s writing, I would like to begin with the joy she takes in washing her hair. Kyger says that her poem Tuesday, October 28, 1969, Bolinas was written with a ‘tongue and cheek quality.” The excitement of living in San Francisco and traveling abroad had been replaced by days of puttering around the house, only relieved with a walk into nearby Bolinas. Bored as she slowed down to meet the pace of her new, more rural life, Kyger responded with comedic irony. But most importantly Kyger was, in her own words, “discovering a simple voice to describe unadorned times.”

And now I’m looking forward / to washing my hair are the final lines of the poem mentioned above. What could be simpler and more pleasurable than water running through her hair? This simple act illustrates a powerful stream in Kyger’s poetry, and that is her relationship to water.

Though I am speaking in the broadest terms without distinguishing fresh water / salt water / to swim in / to travel one / to wade in / to sit by, indeed all the permutations of water that we find in Kyger’s poems, this current is a powerful force in the upwellings of poetic language in her first book, The Tapestry and the Web, the poetic aftermath of her years in Japan and her travels through India.

‘When I returned a second time here there was an evening sun

and I swam ashore

and crouched in the thickets’

(As Ever, p 32)

Like Odysseus, Kyger came home to San Francisco a second time. Having left her first husband Gary Snyder to return to the Bay Area, Kyger is both Odysseus and Penelope. Kyger’s past like theirs past is swept up in the present of this poem the and loutish behavior of suitors: quit eating the coffee cake and cottage cheese / put the lid on the peanut butter jar / sandwiches made of cucumber, stop eating the food! (p 35). Mixing the mythic, impersonal past into a very personal now, Kyger remains true to her orchestration of these voices and brings us their wisdom and joy.

Sometime shortly after Kyger’s writes her lovely poem to Ganesha, she moves to Bolinas. It is at this point that her myths stop leading her poems. Instead they erupt in the fragments of her notebook or are assimilated into objects:

wood

sweep

ocean

music

It’s getting figured out

shells

wood

notes

Kyger is not a naïve empiricist who is confusing the word with the object. She is speaking of the relationship of words with the unexpected or paradoxical. The relationship can also be as clear as shells to the ocean. This poem’s koanic quality above all offers us a way of seeing the relationship of the various objects that arise from her unconscious and subconscious to each other.

Some people are natural novelist. They exaggerate, twist, distort, and lie to bring some greater pleasure—and we hope some greater truth—to an audience. Kyger is a truth teller. Her instinct for the unvarnished truth as she sees it is laid out for all to see in Strange Big Moon: The Japan and India Journals 1960-1964. Too often followers of the beats whom she traveled with, Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsburg and Peter Orlovsky, have gathered their material into counterculture hagiographies. Kyger gives us the brilliant observation of the day to day difficulties of these strong personalities getting along. It is above all human and humane. Caught unprepared for a storm on Descheo Island in 1971, Kyger and her Caribbean cheechakos lose such precious items as Peter’s thesis, Margot’s hiking boot and Joanne’s cigarettes to the “30 feet dark silver monsters (p 126)” of a serious tropical storm that inundate their campsite on the beach. Kyger’s impression as written in this poetic sequence is she won’t survive the island. Of course she does, but that’s the way she feels and there’s good reason for it.

Though Kyger continued to travel, to teach, to give readings and an occasional trip to Mexico, her sense of Bolinas as her place and a love of the fine details of daily life become more and more intertwined. I want a smaller thing in mind / Like a good dinner / I’m tired of these big things happening / They happen to me all the time (pg 134).

Of course Kyger’s Bolinas is anything but small. By her garden, the Bolinas ecosystem, her relationship to people, friends or otherwise, her relationship to herself and religious / mythical / philosophical subjects such as the origin myths of her local Miwok Native Americans, Buddhism, Christianity or Descartes, Kyger informs us with day by daybook poetry that doesn’t declares where it is starting so much as it begins where it begins:

And I know this is my focus to meander

For days around the calendulas

Now happily reseeded next to their roots

(As Ever p 194)

Kyger’s meanderings are focused. March 7, Wednesday Palenque 1985, one of two pieces from her collection Phenomenological from As Ever, Kyger’s selected works, revels in the presence of an ‘iridescent blue butterfly’ and fourteen toucans that are the joyful natural foreground that naturally includes mention of a river running below the ruins. Her ambivalence to human presence we find in the excited North Americans who say “What’s the name of this place?”, sharing with us their joy and ignorance, and the noisy, aggressive Germans we find in the poem March 8, Thursday. Here the ruins are a backdrop most of all for “friend butterfly / is back in brown and red and yellow / the most beautiful guard / of this temple (As Ever, p 233).

Though Kyger is disturbed or upset by human failings, by nature’s lack of voice in the counting rooms of capitalism, her writing as she grown older offers heartfelt elegies for important figures in her life like Larry Eigner, Chogyam Trumpa or the wonderful piece on her once-close friend Richard Brautigan that never says Brautigan dies, or that his life went off the tracks, but rather Kyger has finished reading a biography of Somerset Maugham, who dies at 92 “—terrified, lonely, crazy, no religion” (p 234).

A friend she’s giving a ride to says, “I think a tragedy has occurred.” The Sheriffs are in front of Brautigan’s house. In the poem Joanne says, “Well he’s gone / away, maybe / a robbery . . . “. Maugham suffers terrible before he dies. There is an intimation of tragedy, but it is not recognized. There is so much depth in all of Kyger’s elegies, of which there are a number. I suppose that’s the fate of poets who live long enough to write their missing friends.

Two formidable influences run through the course of Kyger’s work. The first is that of Charles Olson’s Projective Verse. The first I will mention is that energy is moved by the poet from the poem to the reader. That the field of composition is a piece of paper, and the age we live in allows us to physically arrange a poem according to the demands of “the HEAD by way of the EAR, to the SYLLABLE (Olson 2) and “the HEART by way of the BREATH, to the LINE.” But more importantly—and more specifically, Kyger has taken these following words of Olson to heart:

It comes to this: the use of a man, by himself and thus by others, lies in how he conceives his relation to nature, that force to which he owes his somewhat small existence. If he sprawl, he shall find little to sing but himself, and shall sing, nature has such paradoxical ways, by way of artificial forms outside himself. But if he stays inside himself, if he is contained within his nature as he is participant in the larger force, he will be able to listen, and his hearing through himself will give him secrets objects share. And by an inverse law his shapes will make their own way. It is in this sense that the projective act, which is the artist’s act in the larger field of objects, leads to dimensions larger than the man. (Olson 4)

We can see on reading Kyger’s work much of her life has been dedicated to understanding the human relationship to nature and creating work larger than the human beings. This is not to obscure her dedication to creating mythology poems, such as Jakata Tales, Adonis is Older than Jesus, or From the Life of Naropa which as inevitable a nod to one of her mentors, Robert Duncan.

Ron Silliman said in an email to the poet and critic Linda Russo some years ago, “She’s one of our hidden treasures — the poet who really links the Beats, the Spicer Circle, the Bolinas poets, the NY School and the language poets, and the only poet who can be said to do all of the above.” High praise indeed. But aside from being a nexus of various schools, Kyger is above all a poet to be praise, who has followed her path so as to open a field of understand for her readers, a field that is both a page and the dry, yellow grasses of the Marin County hillside that children in my time slid down on cardboard.

In closing there are two pieces I would like to share with you. This discussion of Kyger’s work began with her hair, which then traveled a part where I see Kyger as both Odysseus and Penelope in her Odyssey. Her poem Ocean Parkway Gazing returns us once again to the natural world. Kyger is sitting near the ocean listen to the waves and writing her poem. The first section describes the natural world in incredible detail. The second part tells us how this scene came to be and with what the journey will be mapped, and it is here we will start.

The voice describes the scene

looks up for reference

listens to two

songs sparrows carry out

their call

And response as the hissy light

waves roll over changing continuum.

The minutes go by the sea

The sea closes in

Up to the edge

of mythology.

To balance our serious discussion of the religious and mythological, I leave you with the levity of the poem Phillip Whalen’s Hat.

I woke up about 2:30 this morning and thought about Philip’s hat.

It is bright lemon yellow, with a little brim

all the way around, and a lime green hat band, printed

with tropical plants.

It sits on top

of his shaved head. It upstages every thing & every body.

He bought it at Walgreen’s himself.

I mean it fortunately wasn’t a gift from an admirer.

Otherwise he is dressed in soft blues. And in his hands

a long wooden string of Buddhist Rosary beads, which he keeps

moving. I ask him which mantra he is doing – but he tells me

in Zen, you don’t have to bother with any of that.

You can just play with the beads.

Bibliography

e-mail to Linda Russo by Ron Silliman

http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/authors/kyger/silliman.html

Kyger, Joanne, As Ever. Penguin Books, New York, New York. 2002

Kyger, Joanne Phil Whalen’s Hat from Just Space: poems, 1979-1989 (Santa Rosa: Black Sparrow Press, 1991) http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/philip-whalen-s-hat/

Olson, Charles, Projective Verse http://www.poetryfoundation.org/learning/essay/237880

Jeffrey Kahrs

Seattle, WA