Daphne Marlatt was kind enough to allow us to publisher her Levertov Panel notes:

Denise Levertov: Poet of Inter-Relations

(by Daphne Marlatt)

A few weeks after I’d turned 21 I had the opportunity to ask Denise Levertov a question vital to me as a young writer. This was during the remarkable 1963 summer school at UBC, which somehow got redubbed the Vancouver Poetry Conference. Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg were the featured discussants, readers, and seminar leaders, while Denise Levertov and Margaret Avison appeared more briefly. Poetry was a male sphere, I learned, studying it then, the Great Poets, both in the tradition and in contemporary time, were men. Women were readers. Yet I was one of a number of young women who were writing at UBC then, Gladys Hindmarch, Judith Copithorne, Maxine Gadd to name those I was closest to, and here was Denise Levertov who gave such a moving, dynamic reading in her slightly reserved voice with its traces of English accent, a reading that affected the audience hugely. So she was something like a mythic figure I somehow found myself sitting beside in the UBC Cafeteria over coffee.

I knew she was married and had a son, I knew she had published several books of poetry that were highly regarded, that she had a poetry connection with Duncan as well as Olson and Creeley. At that point, I had published a few poems in Raven, the campus mag, I was on the fringes of the Tish group and one of the younger poets slated to take over editing Tish that fall as the Tish Poets were leaving for further graduate work or teaching jobs. And I was marrying my high school sweetheart. A well-known writer on the faculty of the English Department had said to me, when I told him about my upcoming marriage, Oh that will be the end of your writing then, and this worried me. I relayed his comment to Denise who laughed and said most emphatically, What nonsense! I’ve been married for a number of years and I’m very much writing and publishing.

This was my first moment of experiencing feminist solidarity with an older woman poet. At that time Denise Levertov would have been on the edge of turning 40, almost a generation older than me. It was something I never forgot: her sureness, the same sureness I’d heard in those singular tones of her reading voice with its careful articulation. The voice of someone who paid careful attention to what was both around and within her.

It’s that careful attention I still hear in her poetry, even her earliest poems, even her later sad or most questioning ones when she is doubting the possibility of faith. And of course it is evident in her protest poems. A sureness of perception on one hand and of ethical principle on the other, even when a poem suggests a largeness of vision beyond articulation.

Back then I would have been reading her 1961 collection, The Jacob’s Ladder, its title poem giving me a sense not only of the difficulties of writing – ‘and a man climbing/ must scrape his knees, and bring/ the grip of his hands into play” – that masculine image of craft and struggle that in its next lines offers the double-edged comfort of – “The cut stone/ consoles his groping feet” before opening into a return to the descending angels of the preceding stanza – “Wings brush past him” and the final line that opens into pure possibility “The poem ascends.” For Levertov, her poems continued to ascend, through the conflicts of her time, towards a difficult balancing act between a transcendent sense of joy and this-world struggle with despair, between the necessity of political action or at least its articulation and the luminous natural world sensed through our still presence within it.

Her childhood in England, her close attention to waterways (she almost drowned in one falling off a bridge), her Welsh mother’s prompts to pay close attention to flowers and plants, naming them for her, all this I think was deeply ingrained throughout her work in its attention to detail and especially in her later poems to the birds, trees, waterways, and of course her holy mount, Mount Rainier, of this region. Her focus is not so much on isolate objects as on their inter-relations, just as it was very much about the relations, even the most unconscious ones, between very different individuals, awareness of how we are connected. For instance, the lines that conclude the first of her Eichman Trial poems in The Jacob’s Ladder –

He stands

isolate in a bulletproof

witness-stand of glass,

a cage, where we may view

ourselves, an apparition

telling us something he

does not know: we are members

one of another.

Even at her angriest, her most politically acute, this awareness of the connection between what could be seen as diametrical opposites is present. In her long political sequence of the late 60s, early 70s, “Staying Alive,” she writes in the tight lines of one of the “Entr’acte” poems how “Heart’s fire/ breaks the chest almost,/ flame-pulse,/ revolution,” and follows that with “Heart’s river,/ living water,/ poetry,” to conclude with how “the singing” of both is actually intermeshed with “the pain of living.” This is very honest, candid poetry written from deep within her own struggle with the political events of the 1960s and early 70s in which she felt, along with so many others, deeply implicated — as we all are in the struggles of our time, whether we’re conscious of it or not. The collagist approach of “Staying Alive,” alternating between prose excerpts from impersonal news reports and personal letters interfaced with lyric passages, seems not only very much of that moment but also strangely contemporary in its sense of urgency.

The contraries she keeps putting together, the dark and the light, the individual and the nation, luminous attention and dark indifference, continue to mark many of the late poems of Evening Train (1992). “In California During the Gulf War” with its stark realities of both “that huge cacophony” of the war and the blossoming landscape at hand concludes with the recognition that

No promise was being accorded, the blossoms

were not doves, there was no rainbow. And when it was claimed

the war had ended, it had not ended.

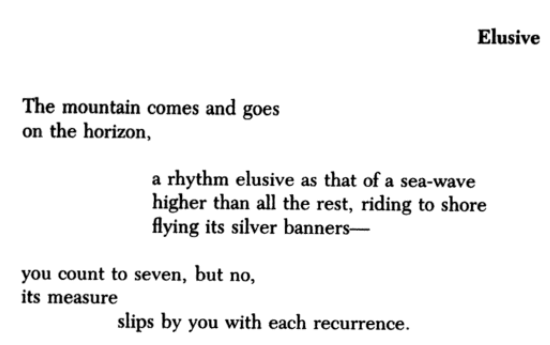

Yet I still hear that sureness of perception with its harmonic of joy and how carefully she notates it in “Elusive,” one of her Mount Rainier poems:

That visual shift on the page from mountain to sea is also a tonal shift, then back to counting as if that were something solid, and forward again to the watery shift of “slips by you with each recurrence.” The transition from seen to unseen translated into movement on the page.

I can’t end these comments on the acuity of her perceptions, including those on the process of composition, without mentioning how important her comments on pitch and notation were to me in her essay “On the Function of the Line.” When she was reading her work aloud you could hear those “sea-wave” movements of her lines in her steady attentiveness to the movements of both meaning and rhythm.

This is my sense of Denise Levertov, poet of careful attention to dualities, taking the separate measure of each yet working always towards their interrelation. There is a poem in Evening Train which seems to me to articulate her largest vision of this. It is a synthesis of physics, sentient experience, and spiritual understanding, along with a crucial acknowledgement of the limitations of language. (Read “After Mindwalk,” p. 105.)

After Mindwalk

Once we’ve laboriously

disconnected our old conjunctions –

‘physical’, ‘solid’, ‘real’, ‘material’ – freed them

from antique measure to admit what,

even through eyes naked but robed

in optic devices, is not perceptible (oh,

precisely is not perceptible!): admitted

that ‘large’ and ‘small’ are bereft

of meaning, since not matter but process, process only,

agthers itself to appear

knowable: world, universe –

then what we feel

in moments of bleak arrest,

panic’s black cloth falling

over our faces, over our breath,

is a new twist of Pascal’s dread,

a shift of scrutiny,

its object now

inside our flesh, the infinite spaces discovered

within our own atoms, inside the least

particle of what we supposed

our mortal selves (and in and outside,

what are they?) – its object now

bits of the Void left over from before

teh Fiat Lux, immeasurably

incorporate in our discarnate, fictive,

(yes, but sentient,) notion of substance,

inaccurate as our language,

flux which the soul alone

pervadess, elusive but persistent.

Daphne Marlatt