We’re still recovering from the very successful Cascadia Poetry Festival which SPLAB conceived of and hosted this past weekend. This week in the Living Room we’ll share our best memories of the just-concluded fest, discuss plans for future iterations and leave plenty of time for critique of your new work. Paul Nelson pinch hits for his wife Meredith who is busy with 9 day old Ella Roque Nelson. He’ll discuss his thoughts about innovative Cascadia poetry and Robert Duncan’s distinction between poetry as an event or as the record of an event.

We’re still recovering from the very successful Cascadia Poetry Festival which SPLAB conceived of and hosted this past weekend. This week in the Living Room we’ll share our best memories of the just-concluded fest, discuss plans for future iterations and leave plenty of time for critique of your new work. Paul Nelson pinch hits for his wife Meredith who is busy with 9 day old Ella Roque Nelson. He’ll discuss his thoughts about innovative Cascadia poetry and Robert Duncan’s distinction between poetry as an event or as the record of an event.

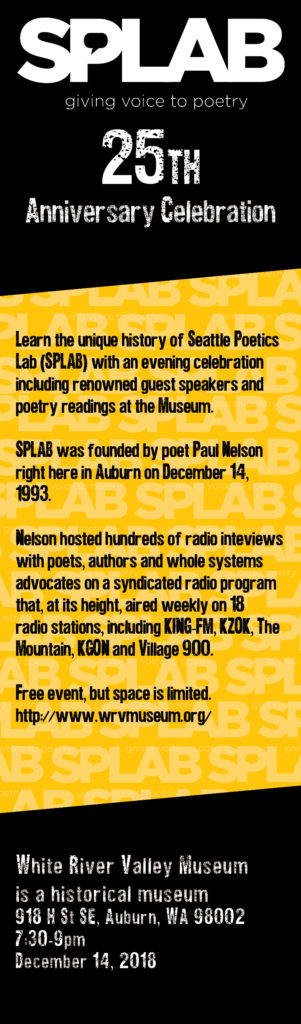

Writers of all ages, backgrounds and skill levels gather Tuesdays at 7P to read new work, the work of someone else or to just be in the engaging company of other writers. Your donation of $5 helps SPLAB continue our programming. Please bring 8 copies of the work you plan to read. Copies are no longer provided by SPLAB.

Living Room happens @ SPLAB in the Cultural Corner at 3651 S. Edmunds. (Look for the SPLAB sign on the wall and come inside.) We’re 2 blocks from the Columbia City Link Light Rail Station. (Parking is available on the school grounds.)

Notes on Poem as Event or as Record of Event (SPLAB Living Room, March 27, 2012)

Jiddu Krishnamurti – To meditate implies seeing very clearly and it is not possible to see clearly, or be totally involved in what is seen, when there is a space between the observer and the thing observed. That is, when you see a flower, the beauty of a face, or the lovely sky of an evening, or a bird on the wing, there is space – not only physically but psychologically – between you and the flower, between you and the cloud which is full of light and glory; there is space – psychologically.

When there is that space, there is conflict, and that space is made by thought, which is the observer. Have you ever looked at a flower without space? Have you ever observed something very beautiful without the space between the observer and the thing observed, between you and the flower? We look at a flower through a screen of words, through the screen of thought, of like and dislike, wishing that flower were in our own garden, or saying “What a beautiful thing it is”.

In that observation, whilst you look, there is the division created by the word, by your feeling of liking, of pleasure, and so there is an inward division between you and the flower and there is no acute perception. But when there is no space, then you see the flower as you have never seen it before.

When there is no thought, when there is no botanical information about that flower, when there is no like or dislike but only complete attention, then you will see that the space disappears and therefore you will be in complete relationship with that flower, with that bird on the wing, with the cloud, or with that face.

From Charles Olson, Projective Verse http://www.globalvoicesradio.org/Projective_Verse.html

First, some simplicities that a man learns, if he works in OPEN, or what can also be called COMPOSITION BY FIELD, as opposed to inherited line, stanza, over-all form, what is the “old” base of the non-projective.

(1) the kinetics of the thing. A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it (he will have some several causations), by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader. Okay. Then the poem itself must, at all points, be a high energy-construct and, at all points, an energy-discharge. So: how is the poet to accomplish same energy, how is he, what is the process by which a poet gets in, at all points energy at least the equivalent of the energy which propelled him in the first place, yet an energy which is peculiar to verse alone and which will be, obviously, also different from the energy which the reader, because he is a third term, will take away.

This is the problem which any poet who departs from closed form is specially confronted by. And it involves a whole series of new recognitions. From the moment he ventures into FIELD COMPOSITION— put himself in the open— he can go by no track other than the one the poem under hand declares, for itself. Thus he has to behave, and be, instant by instant, aware of some several forces just now beginning to be examined. (It is much more, for example, this push, than simply such a one as Pound put, so wisely, to get us started: “the musical phrase,” go by it, boys, rather than by, the metronome.)

(2) is the principle, the law which presides conspicuously over the composition, and, when obeyed, is the reason why a projective poem can come into being. It is this: FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF CONTENT. (Or so it got phrased by one, R. Creeley, and it makes absolute sense to me… (tho Levertov suggested FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN A REVELATION OF CONTENT,which seems more accurate, Ed).

Now (3) the process of the thing, how the principle can be made so to shape the energies that the form is accomplished. And I think it can be boiled down to one statement (first pounded into my head by Edward Dahlberg): ONE PERCEPTION MUST IMMEDIATELY AND DIRECTLY LEAD TO A FURTHER PERCEPTION. It means exactly what it says, is a matter of, at all points (even, I should say, of our management of daily reality as of the daily work) get on with it, keep moving, keep in, speed, the nerves, their speed, the perceptions, theirs, the acts, the split second acts, the whole business, keep it moving as fast as you can, citizen. And if you also set up as a poet, USE USE USE the process at all points, in any given poem always, always one perception must must must MOVE, INSTANTER, ON ANOTHER! So there we are, fast, there’s the dogma. And its excuse, its usableness, in practice. Which gets us, it ought to get us, inside the machinery, now, 1950, of how projective verse is made…

And the threshing floor for the dance? Is it anything but the LINE? And when the line has, is, a deadness, is it not a heart which has gone lazy, is it not, suddenly, slow things, similes, say, adjectives, or such, that we are bored by? For there is a whole flock of rhetorical devices which have now to be brought under a new bead, now that we sight with the line. Simile is only one bird who comes down, too easily. The descriptive functions generally have to be watched, every second, in projective verse, because of their easiness, and thus their drain on the energy which composition by field allows into a poem. Any slackness takes off attention, that crucial thing, from the job in hand, from the push of the line under hand at the moment, under the reader’s eye, in his moment. Observation of any kind is, like argument in prose, properly previous to the act of the poem, and, if allowed in, must be so juxtaposed, apposed, set in, that it does not, for an instant, sap the going energy of the content toward its form…

Robert Duncan from Bending The Bow…

Roethke from North American Sequence